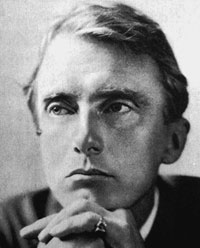

Edward Thomas and Three Women: Helen Thomas

Helen is the one who matters: her devotion and loyalty to Edward Thomas must move all but the stoniest heart.

Helen Noble, the daughter of the journalist, James Ashcroft Noble, was born in Liverpool on 11th July 1877. Noble, who found work writing for The Spectator, moved the family to London in 1880.

After an education at Wintersdorf School in Southport, she became a nursery governess in Rotherfield. She was quite 'bohemian' in dress and in the circles she moved in.

She met Edward through her father who encouraged his writing and their getting to know each other.

Helen became pregnant with Merfyn while Edward was an undergraduate at Oxford .( See my blogs on Oxford.) In 1896, they married and times were very hard financially. Bronwen was born and became quite ill with their poor living conditions, as Edward struggled to make a living by his writing.

Helen taught kindergarden children at Beadles, a progressive co-educational boarding school in Steep where they had moved. They had a third child, Myfanwy, who became a writer.

Under Storm's Wing.

Helen Thomas - using Helen's words.

The problem with Helen is of course also the bonus - she had written her account of her life with Edward in the moving and still widely read works, As It Was and World Without End, 1926 and 1931 collected as Under Storm's Wing.

(I was interested to read that the major Thomas scholar Edna Longley came to Thomas 's poetry after reading Helen's work.)

Helen's daughter, Myfanwy, claims the books were written as a form of therapy to lift the depression which settled over her after the death of her husband. Helen was dedicated to keeping Edward's name and work to the fore, but she also developed a wide circle of friends in the arts, especially music and ballet. She recorded and introduced Edward's poems at the age of 88, and died in 1967.

'Under Storm's Wing' was a way of keeping Edward alive for her, and it is an intelligent, passionate work; in it Helen often belittles her intellect and wisdom, sadly, something she had probably evolved under Edward's frequent unkindness.

I depended heavily on 'Under Storm's Wing' and decided to have Helen in the first person - the voice I give her is not that of Helen in her book - it needs to have that sense of happening in the present which Jude Morgan referred to in his commentary on 'The Secret Life of William Shakespeare'.

But I chose to have her write a memoir, 'Half a Kiss, Half a Tear' and to open and close it with scenes and phrases taken very closely from Under Storm's Wing. Here is an extract set in Leddington:

We’d been in Leddington for ten days and I’d scarcely talked to Edward alone in

all that time. I suggested that we Thomases go out together and leave Mr and

Mrs Chandler in peace as they had a great deal to do before he left for his

regiment. Edwy was cheerful and seemed happy to be with us that day.

We passed through the orchard where the tree

branches were propped to support the fruit. We gave the bee-hives a wide berth

and headed for Ludstock brook where Myfanwy could paddle. Merfyn and Bronnie

were simply glad to have us all together.

Sometimes I felt I was no more to Edward

than his children’s mother. We were never alone here. At mealtimes the

Chandlers and the children were with us, and for so much of the rest Edward and

Robert, and sometimes the other two poets who lived nearby, went walking

together discussing poetry. Well, I trusted they knew how lucky they were to

have the best critic and reviewer in England with them.

I was glad to see Edward happy again,

after the horrors of the year before, of course I was. Only —oh, I was

disappointed with the holiday, but I didn’t want to show it. Edward could be so

cold if I importuned him like that.

My mind was full of–– uncertainties. I

could generally accept life and its changes without too much fuss. I’d had to

the year before, when Edwy was so wretched and scarcely ever at home. I’d

wanted him, longed for him. The loneliness ate my heart away, and yet I’d fear

him coming, because I always hoped for too much. I’d have the house gleaming

and a lovely meal and the garden free of weeds and so of course expect

everything to be happy. And then I would, over and over again, be disappointed

and shocked by real life, the real life we were living. By his dark moods. The

truth was, he had friends who could work those sorts of wonders for him; their

homes were opened to him, beautiful homes, which he described to me in letters,

lovely houses by the sea or in the mountains. No wonder it was good for him to

get away from me and our plain cottage life.

Still, in spring he had come home to stay and

he was happier, although money was always an anxiety. We had the holiday

boarders from Bedales and somehow we managed. We had worked together on the

garden, planting things for the future: an apple tree a friend had given him

for his birthday, some asparagus crowns.

But now the war and the idea of going to

America with the Frosts.Edward saying

that there would be no market for his kind of writing in England - we had to talk about it. He would vacillate to and

fro about America. I could foresee that – but not the outcome. Could he even be

thinking of leaving us behind?

We arrived at the brook, poor panting

Rags wading in first and lapping away. We sat on the bank amongst the willow

and alder trees and talked. When Edward’s mood was so light and untroubled I

was loathe to risk breaking it with my questions, but I had to.

‘This plan about America, Edwy – tell me

what you’re thinking.'

Helen's voice: She wrote many

hundreds of letters and if I tried to emulate her voice it is the voice of the

letters, not because they were contemporary rather than retrospective (after

all 'Half a kiss, half a tear' is meant to be a memoir) but because they are

less polished, more spontaneous and so more easy to contemporary ears than

Helen's prose in Under Storm's Wing. Sometimes it is rather too fulsome and I

do try to capture that from time to time. But mostly it is

sincere, vivid and moving and I know I can't attempt to equal it . Look at this

on their final parting:

"I sit and stare stupidly at his luggage by the walls. He

takes a book out of his pocket. 'You see, your Shakespeare's Sonnets is already

where it will always be. Shall I read you some?'; He reads one or two to me. His

face is grey and his mouth trembles, but his voice is quiet and steady. And soon

I slip to the floor and sit between his knees, and while he reads his hand falls

over my shoulder and I hold it with mine. "I sit and stare stupidly at his luggage by the walls. He

takes a book out of his pocket. 'You see, your Shakespeare's Sonnets is already

where it will always be. Shall I read you some?'; He reads one or two to me. His

face is grey and his mouth trembles, but his voice is quiet and steady. And soon

I slip to the floor and sit between his knees, and while he reads his hand falls

over my shoulder and I hold it with mine.  I hide my face on his knee and all my tears so long kept

back come convulsively. I cannot stop crying. My body is torn with terrible sobs.

I am engulfed in this despair like a drowning man by the sea. My mind is

incapable of thought. I hide my face on his knee and all my tears so long kept

back come convulsively. I cannot stop crying. My body is torn with terrible sobs.

I am engulfed in this despair like a drowning man by the sea. My mind is

incapable of thought.

So we lay, all night, sometimes talking of our love and

all that had been, and of the children, and what had been amiss and what right.

We knew the best was that there had never been untruth between us. We knew all

of each other, and it was right. So talking and crying and loving in each

other's arms we fell asleep as the cold reflected light of the snow crept

through the frost-covered windows."

Here is part of a letter to Robert thanking him for succeeding in getting Edward's poems published in America. It was written near the time Edward was killed:

High Beech

March 2. Late at night [1917]

Dear Robert

What a bit of luck to get your letter at all. I thought all the mails had gone down in the Laconia, but evidently not. I'm so excited & happy about your splendid news, & I've already written to the dear man & told him, & to John Freeman to find out about those 'insists'. I feel sure it will be all right. I'm not at all sure that Edward Eastaway will consent to be Edward Thomas, but I will add my 'insists' to yours & hope for the best. Also I like the idea of your preface & feel sure he will too. It's all very good news & you sound as pleased & you knew we would be.

By now you will have heard from him. He's at Arras & expecting a hot time presently. I don't suppose I can tell you much about him may I. He's at present at head quarters as adjutant to a ruddy Colonel whose one subject is horse racing & jockeys & such & with whom our man gets on so well that the he's longing to be back at his battery, he's afraid the Colonel has taken a fancy to him & will keep him. It will probably mean promotion, but Edward wants the real thing & wont be happy till he gets it & what is one to do with such a poet. In a pause in the shooting he turns his wonderful field glasses on to a hovering kestrel & sees him descend & pounce & bring up a mouse. Twice he saw that & says "I suppose the mice are travelling now". What a soldier. Oh he's just fine, full of satisfaction in his work, & his letters free from care & responsibility but keen to have a share in the great stage when it begins where he is.

At first after we'd said 'Goodbye' & we knew what suffering was, & what we meant to each other, I did not live really, but just somehow or other did my work, but with my ears strained all the time for his step or his coo-ee in case he came back. But the one can only wait & hope & not let panic take a hold of one, his happy letters & the knowledge that all is so well between us, are making life life again, & the Spring helps too & the feeling that the end is near-must come soon, & that that end will be-if it is at all-a beginning again for us with such knowledge of each other as nothing can ever obliterate, nothing can ever, that is what we know & what makes life possible now.

I must tell you that [the] last evening we were talking of people of ourselves of friends & of his work & all he'd like done. And he said "Outside you& the children & my mother, Robert Frost comes next." And I know he loves you.

She enclosed one of these photographs taken by Merfyn, probably the High Beech.

|

|---|

At Steep 1916

People don't like it because they say he is too much a soldier here, & not at his best. But I send it thinking that you know him so well you'll be able to read him into it, if he is not there to you.....

Edward will be 39 tomorrow March 3rd, & we are hoping our parcels of apples& cake & sweets & such like luxuries will get to him on the day. Our letters take a week to reach him. Yours not much longer I expect.

Two weeks later.

I've kept & kept this letter & just have not had the opportunity to add to it. You've heard by now I expect from Edward & perhaps from Mr. Ingpen too. Eastaway will not be Thomas & thats that he says, but all about the 'insists' you'll have heard from others. Edwards letters are still full of interest & life & satisfaction in his work. He's back on his battery now in the thick of it as he wanted to be, firing 400 rounds a day from his gun, listening to the men talking, & getting on well with his fellow officers.He's had other times of depression & home sickness. He says "I cannot think of ever being home again, & dare not think of never being there again" & in a letter to Merfyn he says "I want to have six months of it, & then I want to be at home. I wish I knew I was coming back." Oh if only I knew that too!*Poem: It has to be this, which I think was a valediction to Helen and shows as much love as Edward was capable of showing.

And You Helen.

And you, Helen, what should I give you?

So many things I would give you

Had I an infinite great store

Offered me and I stood before

To choose. I would give you youth,

All kinds of loveliness and truth,

A clear eye as good as mine,

Lands, waters, flowers, wine,

As many children as your heart

Might wish for, a far better art

Than mine can be, all you have lost

Upon the travelling waters tossed,

Or given to me. If I could choose

Freely in that great treasure-house

Anything from any shelf,

I would give you back yourself,

And power to discriminate

What you want and want it not too late,

Many fair days free from care

And heart to enjoy both foul and fair,

And myself, too, if I could find

Where it lay hidden and it proved kind.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Episode 1 Don't forget! I was interviewed as part of this but whether or not - it will be marvellous. Matthew hugely insightful and Robert MacFarlane reading Thomas's poems.

1/3 Matthew Oates follows in the footsteps of the writer Edward Thomas.

First broadcast: 29 Mar

2013

- Next Friday 15:30 BBC Radio 4

Really enjoying your blog Margaret, I'm learning more and more about my great-grandparents and their family. I find the social history of that time fascinating and humbling; here I am living my comfortable life, virtually in parallel, 100 years later. Like you, I'm looking forward to the "In Pursuit of Spring" programme, but don't want to hear my voice!

ReplyDeleteLucy

Thank you Lucy. I'm so glad you are on the Fellowship Committee - a fresh empathic voice with a unique point of view as 'family'.

DeleteAbout the broadcast - not sure whether I'm hoping or dreading inclusion. I know I was tongue-tied at Matthew's perfectly reasonable question, 'What does Edward Thomas mean to you?' Just didn't know where to start, and of course have thought of great responses answers since! You will be fine.

I have written a short article about Edward Thomasfor a forthcoming issue of Trowbridge Civic Society newsletter. I mention The Pursusit of Spring, Broughton Gifford, Tellisford and Dillybrooke Farm, places which are near to the town. By chance I discovered that a person is putting hundreds of photos of Trowbridge on Flickr and there are several of the Royal Garrison Artillery. Do you think that any of the officers in the photograph I have linked to below might be Thomas?

ReplyDeleteAlso, is there mention of Trowbridge in your novel?

Peter Collier

http://www.flickr.com/photos/93838966@N02/8539427765/sizes/k/in/set-72157632943754506/

Hello Peter,

DeleteThank you for the picture of officers at Trowbridge.

How interesting.

There is a further picture of Thomas in uniform and he does look like the chap second from the left on the bottom row of the picture - but I can't be sure. I'll try to send to Richard Emeny of the ET Fellowship.

Yes I have mentioned Trowbridge in my novel as he was stationed and trained there. If I had your email I could send you the extract-or I guess you could buy the book.

Best wishes

Margaret

Thanks.I do intend to buy the book. I recently read "Now all roads lead to France" and Thomas has been one of my favourite poets for a long time. It would be fascinating if the photograph did show Thomas as I haven't seen it elsewhere. There are one or two other photographs in that collection, but one is 1917, probably after Thomas left and the other is of a football team!

ReplyDeleteMy email address is pcollier@blueyonder.co.uk

Peter Collier

ugg outlet

ReplyDeleteralph lauren outlet

ralph lauren

coach outlet

kate spade outlet

nfl jerseys wholesale

air max 97

coach canada

moncler jackets

christian louboutin outlet

cc20180930

michael kors handbags

ReplyDeletegolden goose

stephen curry shoes

curry 4 shoes

air max 97

jordan retro

air max 2019

nmd

ralph lauren uk

adidas nmd

supreme outlet

ReplyDeletegoyard bags

adidsas yeezy

yeezy

balenciaga

goyard handbags

adidas yeezy

yeezys

goyard

golden goose

liiaocj56k21

ReplyDeletegolden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

supreme outlet